De Oostende-Dover lijn was eind jaren 1880 vastberaden de vloot uit te breiden met grotere en snellere schepen zoals de Princesse Joséphine en Princesse Henriette. De oudere paddelstomers haalden maar een snelheid van 16 knopen terwijl de nieuw gebouwde vaartuigen stilaan 20 knopen en meer konden stomen. De oude schepen deden vooral de nachtdiensten en de snelle stomers mochten de dagdiensten verzorgen. Het beoogde doel was om alle afvaarten met snelle schepen te kunnen doen.

De industriële ontwikkeling was ook niet meer tegen te houden. Vooral met de beschikbaarheid van elektriciteit. De scheepswerven bouwden steeds betere vaartuigen met vooral machines die steeds hogere werkdruk aankonden en aldus hogere snelheid konden produceren. De bouw van de Princesse Joséphine en Princesse Henriette waren een groot succes op alle vlakken en de lijn profiteerde van een toename in reizigers en een hoogstaande reputatie als snelle postlijn.

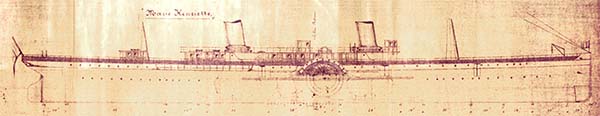

De regering besliste daarom in 1892 om opnieuw twee vaartuigen te laten bouwen die groot, comfortabel en vooral snel waren. Na de ervaringen met de Prince Albert, Ville de Douvres stond de concurrentie tussen Cockerill en Denny Brothers in Dumbarton heel scherp tegenover elkaar. Met de bouw van de “La Flandre” bewees Cockerill een evenwaardige scheepsbouwer te zijn net zoals de wereldbefaamde gebroeders Denny in Schotland. De Belgische staat bestelde daarom aan beide scheepswerven elk een gelijkaardig vaartuig te bouwen met de luxe zoals de vorige prinsessen en vooral de nieuwe technologie inzake kracht en snelheid. De voorwaarden van het contract legde vooral de nadruk om een minimum snelheid van 21 ½ knopen te halen. In eerste instantie wilde men de schepen Rubis en Diamant noemen. Later werd dat de Léopold II en de Marie-Henriette. Beide werven kregen dezelfde technische beschrijving. Denny Bros. begon de bouw van de Léopold II en Cockerill nam een start aan de Marie-Henriette. De schepen hadden een lengte van 340 voet en 38 voet breed met een diepgang van 15 voet. Omgerekend naar metrisch is dat 103.70 m x 11.59 x 4.57 of 0.305 m per voet.

Bijkomende voorwaarde is dat beide schepen samen de proefvaarten voor oplevering en aanvaarding zouden doen in Schotland op hetzelfde traject en onder dezelfde omstandigheden.

Op 3 december 1892 liep de Marie-Henriette bij Cockerill als eerste van stapel (Léopold II op 22 december 1892). De graag geziene echtgenote van Minister Beernaert mocht die zaterdag om 15u00 als meter de knoop doorhakken in aanwezigheid van hooggeplaatste personen. Langzaam begon die namiddag het schip te glijden en gleed gracieus in de rivier terwijl omliggende schepen uitbundig de scheepsfluit lieten horen.

Ook aan de inrichting van het schip was alle aandacht besteed inzake smaak en luxe. In de krant “l’ Echo d’Ostende van 18 mei 1893 verschijnt een mooie beschrijving als volgt vertaald:

“De Marie-Henriette is opgetuigd als een schoener met twee masten. De stomer is slank om grote snelheid te halen. Als afmetingen heeft ze: lengte= 340 voet of 103.63 m – breedte= 38 voet of 11.58 m – hoogte tot aan het hoofddek= 15 voet of 4.57 m – breedte over de tamboeren= 23.50 m – de hoogte tussen de dekken is 2.52 m. Het schip heeft geen centrale kiel noch rollende kiel. Het algemene aspect is echt imposant en het concept doet grote eer aan dhr Rickard, directeur van de werf te Hoboken en zijn ingenieurs. De nieuwe stomer heeft drie dekken. Het hoofddek waar zich de luxe hutten bevinden. Het wandeldek, een ware boulevard met veel faciliteiten waar men ruim kan wandelen. En de commandobrug die enkel voor de dienst is gereserveerd. Op deze laatste bevinden zich de volgend installaties: de hut van de commandant gemeubeld met een simpele elegantie – twee enorme schouwen met zicht op de machinekamer.

We beginnen het bezoek aan het schip op het hoofddek vooraan waar zich de post voor de matrozen, de stokers en een salon tweede klasse voor dames bevinden waar men toegang heeft via een speciale trap. De kamers hebben witte panelen met goud afgelijnd. De meubels zijn luxueus in gepolijst notenhout. Naast het salon ligt een toiletruimte met lavabo. Vervolgens komen we niet ver van de dames aan het salon tweede klasse heren. Deze werden met totaal andere smaak ingericht gezien het verschil in geslacht. Een bar met een ronde toog dat zeer erg geapprecieerd zal worden. Het salon is ingericht zodat er zo’n 100 reizigers kunnen vertoeven. Nog altijd op het hoofddek opslag voor kolen en bagage, de ketels, stookplaatsen en machinekamer. Meer naar achter het salon dames 1e klasse die een speciaal uitzicht heeft en ingericht is met een bijzondere luxe en smaak toegankelijk door middel van een enorme monumentale trap met rijk gekleurd glas in notenhout kaders met artistieke sculpturen in hout dat het houten kader vormt. De meubels in het salon zijn in acajou en de stoelen in fluweel. Achteraan een rijkelijk beklede gesculpteerd marmeren schouw met koper afgewerkt. Het salon is mooi verlicht en opmerkelijk zeer comfortabel. De beschildering is simpel met witte panelen met roze en gouden lijnen. Het geheel zeer behaaglijk. In het herensalon 1e klasse een niet minder aspect. De meubels in notenhout en Marokkaans bruin en met een toiletruimte en 40 couchettes. Wanneer we terug naar boven gaan naar het wandeldek vinden we vooraan de ruimte voor de postzendingen en de keuken met grote afmetingen voor een schip van dit formaat. Vervolgens de machinekamer met grote vensters die toelaten dat de reizigers de werking van de machine kunnen zien. Waarna we aan de boudoir dames komen dat een exclusieve dromerige pracht uitstraalt. De muren zijn in speciaal esdoorn hout en satijn hout. De panelen geschilderd volgens een totaal nieuw procedé met bloemen op een gouden achtergrond. Het is een soort email dat de illusie geeft van mooi leder. De meubels zijn in acajou en fluweel. De reizigers die dit boudoir verlaten wanen zich een dromerige Princes. Maar de impressie die we van het boudoir hebben is niets vergeleken met het grote restaurant. Onmogelijk om nog een betere inrichting voor te stellen met nog meer artistieke inrichting en bemeubeling. Men stelt zich voor een immense zaal met gesculpteerd eiken wanden in zuivere Vlaamse Renaissance en onvergelijkbare artistieke stijl. Achteraan een buffet, nog altijd in gepolijst eiken, met panelen in Delfts blauw. Sculpturen boven de banken en rond het salon met decoratieve en artistieke panelen. Om dit alles te steunen zijn de steunkolommen uitgevoerd in geklopt koper. Ook vermelden we de schouw achteraan in koper en prachtige faience. Een pendule in uitgesneden eik in Vlaamse stijl. Aan beide kanten van de schouw het wapen van Engeland en België.

De mensen die de boot bezoeken, en we overdrijven niet, bevestigen dat dit restaurant schitterend is verlicht met vensters in een schitterende artistieke smaak. Het restaurant bied plaats aan 100 personen die gemakkelijk een maaltijd kunnen nuttigen. In het midden bevind zich een raam dat licht geeft aan het herensalon.

Het restaurant

Van het restaurant gaan we naar boven via een speciale trap op het wandeldek waar zich een tiental private hutten bevinden bemeubeld in eenvoud en elegantie, de rookruimte, de Koninklijke hut en de afdaken. De rookruimte is in acajou met panelen in Delfts blauw dat een garnaalvisser en vrouw voorstelt en enkele andere ambachten. De grootste panelen van waarde beelden het Hotel de la Ville uit, de grote markt in Brussel, de Schelde in Antwerpen, de dijk en het strand van Oostende en een panorama van de werf van Cockerill in Seraing. Deze panelen zijn vervaardigd door Mm. Shooft-Joost en Labouchére uit Delft.

We gaan nu de Koninklijke hut binnen, een echte luxe. Het salon bestaat uit Louis XV palissander met panelen in hand geborduurd granaat in een bijzondere smaak. Het meubilair in de stijl en kleuren alsook zeer ruime slaapkamers dat ook in één ruimte kan gemaakt. De meubels zijn in gepolijst notenhout en Louis XIV stijl. De wanden in gesculpteerd hout met gouden randen met zijde en borduurwerk. De accommodatie voor de bemanning is zeer comfortabel. De hutten voor de commandant en officieren dek en machine, daar we weten dat de chef mecanicien dezelfde rang heeft als een luitenant, zijn mooi en praktisch ingericht.

Het schip zal overal verlicht worden door elektrische gloeilampen. Tijdens de nacht is dit aspect in het restaurant een feeëriek zicht. Alles werd minutieus bestudeerd. De commando’s naar de machinisten worden met een “Chadburn” telegraaf doorgegeven met kettingen zonder einde of antwoord. Er zijn ook spreekbuizen met fluit voor diverse communicatie tussen de commandant en de chef machine die op een bijzonder dek in de machinekamer staat om alle werking te kunnen observeren. Hij zet het monster in vlot gang door een simpele beweging aan de handle die de motor en machines opstart. Voor hem is een bord geplaatst waarop een toerenteller, twee waterdrukmeters, een precisie klok, en drie manometers voor de hoge en lage druk en vacuüm. Wanneer we in de machinekamer komen worden we echt verrast met bewondering voor de perfectie waarmee deze reus met de meeste precisie door één man word bediend. Mr. Frankinoulle, chef mecanicien van de dienst was enkele maanden in Hoboken voor de opvolging van de machines.

Het is het huis van Smeyers, Rang en C° uit Brussel dat de Koninklijke hut en rooksalon heeft ingericht. Het restaurant is door het huis Zech uit Malines en de Compagnie des Bronzes uit Brussel ingericht. De rest van de inrichting is volledig door Cockerill uitgevoerd.

Laten we nu de technische kant van de machines bekijken. We weten dat het schip een enorme snelheid van 21.5 knopen op de testen dient te halen. Of bijna 40 km per uur. Als deze snelheid werd gehaald en zelfs hoger, kreeg de constructeur 18750 Fr. per tiende knoop dat het een hogere snelheid haalde. De uitdaging voor de bouw was dat het schip niet dieper lag dan 9 voet. Wat het gewicht van de motor beperkte. Dit bleek opgelost door dhr Braft, chef ingenieur en mr. Raveu, chef van de génie bureau van Cockerill. De machine, een echt monster, is van het compound type met twee cilinders van 2.13 m slag en respectievelijk 1525 en 2745 diameter. Het blok is in gegoten en gesmeed staal net zoals alle andere onderdelen behalve de cilinders. De arm is in gesmeed en hol staal. De distributie van het systeem is van Waelschart met een zuigerlade op hoge druk en twee met lage druk. De evacuatie van de stoom gebeurt via een buis van 90 cm diameter. De condensatie in een condensator van 1 m² met gekoelde plaat. Een raderwiel heeft elk 9 schoepen van 4.57 m op 1.32 m. De stoom word aangemaakt door 8 cilindrische boilers met elk drie ronde ingangen. 164 m² te verwarmen om een druk van 8 atmosfeer op te wekken en de lucht aan te wakkeren met vier ventilatoren. Er zijn een reeks pompen en hulpmotoren. De machine moet een werkkracht van 8300 pk ontwikkelen. Men verwacht hiermee een snelheid hoger dan de Léopold II en althans 22 knopen te halen. Een snelheid dat nog nooit door een paddelstomer is gehaald.

Deze test heeft momenteel plaats op de klassieke locatie en Clyde in Schotland en men wacht vol spanning op de resultaten. Zoals we laatst zegden, de nieuwe vaartuigen zullen effect hebben op de Oostende-Dover lijn dat de overtocht zal kunnen doen in minder dan drie uur voor een traject van 60 zeemijl. Daarbij word 62 ton kolen verbruikt bij een dubbele reis. De bemanning bestaat uit 50 man waaronder 20 stokers. Met de vijf schepen die nu in dienst zijn (3 van Cockerill en 2 van Denny) zal de Oostende-Dover lijn sneller zijn dan de Calais route. “

Eind maart 1893 was de deadline van beide werven voor de aflevering van hun bestelling. Cockerill had nog een week uitstel gevraagd voor de Marie-Henriette en tijdens de test had de Léopold II een zandbank geraakt en moest nog even in droogdok voor herstelling. Cockerill had ook een verrassing bij het vervoer van de grote boilers van Seraing naar Hoboken. Deze bleken te groot voor het vervoer over de weg en konden enkel per boot getransporteerd. Begin mei werden testen gedaan met de Marie-Henriette waar men zonder schoepen een snelheid van 12 knopen kon halen. Met de schoepen schatte men de 21 ½ knopen te zullen halen. Cockerill wilde geen fouten maken. Op 13 mei bezocht de Graaf van Vlaanderen in Antwerpen nog het schip voordat ze de zee op ging naar Schotland voor de officiële testen in Dumbarton. De testen zouden doorgaan op 20 mei.

Op 21 mei vernemen we in de krant dat de Marie-Henriette de testen met glans heeft doorstaan met 23 knopen tegenover de Léopold II die 22 knopen haalde. Tijdens de test deed er zich een ongelukkig voorval voor. Terwijl de Marie-Henriette op dat moment een voorsprong van 3 km had, raakte het schip een drijvende mast waardoor het bakboord wiel werd vernield en het schip aan een bank diende te gaan liggen. Alles aan de binnenkant van het wiel verdween. Op dat moment draaiden de machines 60 toeren. Achteraf zou ze moeten naar Skelmollie in het droogdok gaan voor een tijdelijke herstelling. Even later voer ze naar Cockerill in Hoboken voor volledige herstelling.De Engelsen waren in hun trots geraakt door de resultaten van de Marie-Henriette. Niemand kon ontkennen dat net voor de impact een snelheid van 23 knopen was gemeten. Meer nog, men moest toegeven dat indien het ongeval zich niet had voorgedaan, de Marie-Henriette nog sneller had gevaren. De Belgische commissie was aan boord en kende onmiddellijk de premie van 100 000 Fr. toe aan Cockerill voor de behaalde snelheid.

De Marie-Henriette werd daarmee immers de snelste paddelstomer ter wereld. Cockerill had dan ook niets aan het toeval overgelaten. Zelfs de kolen de gestookt werden waren van de beste kwaliteit en kwamen uit Gosson-Lagasse.

Ondertussen was de Marie-Henriette naar Antwerpen gevaren. Blijkbaar had de verzekering nog een sleepboot ter hulp gestuurd naar Dumbarton om de Marie-Henriette naar Antwerpen te slepen. Maar omdat de sleepboot maar een beperkte snelheid kon halen, was het de Marie-Henriette die sleepboot naar Antwerpen bracht. Het schip haalde immers nog 15 knopen met een defect wiel.

Na herstellen van de schade hadden nieuwe testen in Dumbarton met glans plaats op 5 augustus. Het weer was niet gunstig om schitterende resultaten te halen. Maar haalde toch 22.2 knopen waarbij de motoren een kracht van 8200 PK ontwikkelden met een druk van 7.385 atmosfeer en 53 omwentelingen. De Léopold II haalde 21.955 knopen. De afstand tussen de twee lichtschepen van de test is zo’n 101 km. Ook was opnieuw de officiële Belgische commissie aan boord. Haar wereldrecord bleef behouden. In de Engelse krant “Evening Standard” erkenden de Brits dat ze eervol zijn verslagen. “Shamefully beaten” .

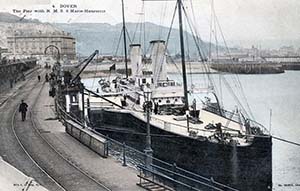

Bij de terugkomst op 8 augustus de dinsdag middag in de haven van Oostende werd het schip met commandant Vandekerckhove hartelijk ontvangen en klonken er 21 kanonschoten. Hierdoor deed het schip haar eerste reis met enkele passagiers op 8 augustus en kwam de Marie-Henriette in dienst op de Oostende-Dover lijn. Voor de prijs van 2 170 000 Bf. kon de Marie-Henriette de vloot vervoegen. De officiële maidentrip is doorgegaan op maandag 14 augustus 1893 om 05u00 ’s morgens met zo’n 300 reizigers. Voor de gelegenheid waren er enkele genodigden van de pers mee die tot in de puntjes door dhr Stracké werden verzorgd. Door de late aankomst van de trein kon de Marie-Henriette pas om 05u12 van de kaai weg maar was toch al om 08u06 aan de Admiralty pier in Dover. Daar hadden de genodigden gelegenheid om enkele bezienswaardigheden te bezoeken voor enkele uren omdat de terugvaart pas om 12u00 voorzien was. Dat werd 12u48 omdat de treinen vertraging hadden en er diende gewacht. Maar met de gunstige omstandigheden op de terugreis langs de kust via Duinkerke, om de reizigers een mooi aanzicht te geven, was men verbaasd om na 2u en 48 minuten de haven van Oostende al te zien. Na aankomst was er nog een feestje met de pers in het hotel Allemagne om de mooie dag op een mooie pakketboot af te sluiten.

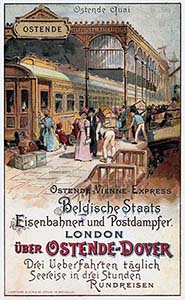

De komst van de nieuwe stomers opende ook nieuwe opties voor de treinreizigers. De Oostende route was de kortste en directste route tussen Londen – België, Duitsland, Zwitserland, Italië (via de Saint Gothard) en Orient. En werkelijk, men kon het traject London-Brussel afleggen in 7 uur. Londen-Keulen= 12 uur – Londen-Frankfurt= 17 uur - Londen-Wenen= 33 uur – Londen-Munchen= 27 uur – Londen-Hanmburg/Berlijn= 22 uur – en Londen-Basel= 19 uur. De administratie van de Belgische spoorwegen paste zijn uurroosters van de grote exprestreinen aan en er werden belangrijke verbeteringswerken in de toegang op de kaai en interne installaties uitgevoerd. In 1893 kon men 96 280 reizigers vervoeren.

Aan de andere kant bleken de problemen met de Léopold II zich op te stapelen. In die mate zelfs dat de staatscommissie het schip aan de gebroeders Denny weigerde. Na één a twee weken in dienst te hebben gevaren viel de machine telkens buiten dienst sinds zijn ingebruikname. Daarom wilde men de Denny Bros. dwingen om grondige wijziging aan de machine aan te brengen en zijn betrouwbaarheid te bewijzen. Men haalde de Léopold II volledig uit dienst. Een nieuw schip moest in zijn proefperiode van zes maanden toch degelijk functioneren.

De Marie-Henriette stoomde verder in dienst maar op 2 september had ze ter hoogte van de South Goodwin banks af te rekenen met defect aan een wiel waar een drijvende paal was in geraakt. Ze was pas om 12u20 afgevaren uit Dover. Het duurde wel even om het euvel te verhelpen en liep pas om 19u00 binnen in Oostende met 280 reizigers aan boord.

Op vrijdag 13 oktober 1893 was de Marie-Henriette ’s avonds 23u45 uit Oostende vertrokken en kwam in botsing met een Deense schoener omstreeks 01u30. De schoener zonk onmiddellijk. Aan boord van de Marie-Henriette was het commandant Fourcault die ter hoogte van de Ruytingen lichtschip de Deense schoener “Eleanor” niet had gezien in de donkere nacht en achteraan op volle snelheid had aangevaren. Men hoorde de Eleanor kraken, rond zijn as draaien en onmiddellijk zinken. Uit het schip kwam zwarte smurrie en kwamen tonnen teer los. De Marie-Henriette had de schoener doorboord ter hoogte van de hut van de 2e luitenant. Deze werd gekwetst maar kon zich nog door een opening naar buiten geraken en zich aan drijfhout vast houden.

Zodra de schok werd gevoeld stopte de Marie-Henriette en werd een reddingssloep in het water gelaten met 1e luitenant Brouckaert en vier matrozen die de drijvende luitenant nog konden redden. Hij was de zoon van de kapitein die samen met vier anderen niet konden gered. De Eleanor kwam uit Duinkerke en voer geen lichten.

Na het ongeval brachten veel schepen vaten teer mee uit zee dat van de Eleanor afkomstig was. Een vat teer had een waarde van zo’n 30 Bfr. Er waren schepen die zo’n 120 vaten konden binnen brengen. Omdat deze eigendom van het vergane schip was, bleek een beloning aan de redders en hun bemanning verschuldigd. Maar dit was hier niet het geval en vertegenwoordigde de vondst voor de redders een mooi sommetje.

Ondertussen verliep de proefperiode van de Marie-Henriette bijna probleemloos. Terwijl deze van de Léopold II maar niet kon beëindigd wegens de vele problemen met de cilinder met als gevolg maanden buiten dienst. (Zie de Léopold II voor meer detail.) Het merkwaardige was dat beide schepen naar dezelfde plannen van de gebroeders Denny gebouwd zijn. Ook de machines.

Het seizoen 1894 stond voor de deur en zeven grote en snelle schepen dienden de dagelijks drie afvaarten te verzorgen. Daar dient wat aandacht aan gegeven omdat de dienstregeling volledig gebaseerd was op trein en post verkeer. Uit de haven van Oostende was een vertrek om – 04u53 , 10u48 en 23u15. Uit de haven van Dover (Admiralty pier) 12u00 middag, 20u00 en 22u15. Ook de druk op de bemanningen die heel wat uren moesten presteren om de opgelegde diensteregelingen uit te voeren. Een werkdag kon meer dan 24 uren duren. Een schip deed vier enkele reizen in drie dagen. Vijf schepen waren dus constant in de vaart om de zes overtochten te kunnen maken. Er diende altijd één schip reserve gehouden om eventueel een dienst over te nemen. Anderzijds was er regelmatig een defect aan de machines die moest hersteld waardoor het schip de geplande dienstregeling niet kon uitvoeren. Resultaat, de problemen met de Léopold II gooiden nogal wat van de geplande dienstregeling overhoop in 1894.

De nog oude nog resterende stomers Prince Baudouin en Parlement Belge geraakten in de schaduw door hun leeftijd en beperkte snelheid. De algemene opinie was dat er nog een nieuw schip zoals de Marie-Henriette moest besteld worden. Tevens moest dat schip in België gebouwd want de scheepswerf van Cockerill had bewezen een waardige concurrent van de Engelse scheepsbouw te zijn. Waarom dan niet in eigen land de vloot laten bouwen. Eind december 1894 stond de Rapide al op de helling bij Cockerill.

Ondertussen was de schroefaandrijving ook al gekend en had de scheepswerf in Dumbarton al een schip op de slede staan met deze techniek. In het buitenland was men al op zoek naar nog andere aandrijfsystemen om nog hoger snelheden te halen. Bij de eerste experimenten haalde men zelfs al 32 knopen met een schaalmodel van 1/25. Op de maritieme tentoonstelling in mei 1894 stonden de scheepswerven Cockerill en Denny samen te pronken met hun realisaties. Cockerill met een model van de Marie-Henriette en Denny met de Léopold II.

In de kamer werd er deftig gedebatteerd over de Oostende-Dover lijn. Op alle vlakken diende er investeringen te komen om de reputatie van de lijn op het niveau te kunnen behouden. Er was nood aan betere haveninfrastructuur, treinstation, technische middelen voor het onderhoud van de schepen. Waarom moest de schepen telkens naar Antwerpen voor het droogdok? Ook waren er te weinig commandanten. De Ministers kregen heel wat kritiek te verwerken. Men had namelijk een troef in handen voor de kritiek. De lijn had namelijk in dat jaar 118844 reizigers, 64389 bagage collies, 77222 postzakken en 237556 pakketten vervoerd. Wat een enorme toename van trafiek betekende.

Op 30 november 1894 had de Marie-Henriette ernstige problemen met de aandrijving van het bakboord wiel. Het schip had op de middag Dover verlaten en kreeg ter hoogte van het Ruytingen lichtschip met schade aan het bakboord wiel te maken. De aandrijving werd verwrongen waardoor het schip moest stoppen, het ganse wiel ontkoppelen en aan kettingen leggen om het vast te maken. Pas dan kon het langzaam verder varen naar Oostende waar het ’s anderendaags om 11u00 aankwam. Er waren 36 reizigers aan boord. Men had al de Prince Baudouin opgewarmd en uitgezonden om de Marie-Henriette te gaan zoeken en hulp te bieden maar de commandant had dit geweigerd. Dit alles deed heel wat inkt vloeien in de pers. Het was schandalig om de reizigers zo te behandelen. Waarom niet zoals de Engelsen de lichtschepen voorzien van radio telegrafische apparatuur? Een communicatie op het lichtschip Ruytingen zou al heel wat info kunnen doorsturen in geval van onregelmatigheden. Ware het niet dat dit lichtschip tot Frankrijk behoorde. Het Marconi systeem deed stilaan zijn intrede in de maritieme wereld. De Marie-Henriette ging als gevolg in februari 1895 bij Cockerill voor drie maanden voor nieuwe sterkere raderwielen omdat er zich teveel problemen voordeden. Op 9 juni was ze terug in dienst.

Eind juni (27/6/1895) had de Marie-Henriette weeral pech en moest op 3 mijl voor anker gaan kort na vertrek uit Dover om 00u30. Een sleepboot uit Dover moest ter hulp gaan en de reizigers dienden over te stappen naar de Prince Albert. De stoompijp was gebarsten en de herstelling kon gelukkig in Dover uitgevoerd zodat de Marie-Henriette terug naar Oostende kon.

Op 14 april 1897 diende de Marie-Henriette naar Antwerpen om een droogdokbeurt te ondergaan. Na enkele dagen kwam ze terug in dienst. In de nacht van 23 op 24 juli 1897 kwam ze in de dikke mist in aanvaring met een ongekend schip. Het bleek een klein zeilschip te zijn dat men hield voor een Frans vissersschip. De Franse pers sprak van lugubere omstandigheden dat een maalboot ter hoogte van de Ruytingen een jacht heeft aangevaren. Een visserschip had op 1 mijl O-NO van de Ruytingen een venster kader opgevist, een kastdeur in acajou en een kleine kast met levensmiddelen. De brokstukken zouden van een jacht komen. Wat verder vonden ze twee gele boeien met de naam “Priny U.Y.F.”. Een derde boei was nog zichtbaar maar kon niet worden opgevist maar daarbij was een lijk dat een jersey vest droeg en rood flanellen hemd. Door de dikke mist kon niet worden verder gezocht en de vondsten werden binnen gebracht op het maritieme bureau. Er was geen twijfel aan de een Belgische maalboot de Priny had aangevaren waardoor ze was gezonken. De Priny bleek een Engels jacht te zijn. Het jacht had tussen 14 en 17 juli het Petit Fort in Gravelines verlaten en er was niets meer van gehoord. De maandag was de Priny nog uit Calais vertrokken om middernacht richting noord. De Marie-Henriette was uit Oostende vertrokken met dezelfde getijde. De aanvaring moest gebeurd zijn niet ver van waar met de lijken had gevonden O-NO van de Ruytingen omstreeks 01u00 ’s nachts. De maalboot kon door de dikke mist het aangevaren schip niet zien noch iemand redden. Achteraf bleek het lijk aan de boei te gaan over dokter Ballue dat aan de jas en hemd werd herkend. Mevrouw Ballue had al een week geen nieuws van haar man ontvangen. Ze was daar niet ongerust over omdat haar man onderweg was naar Aras om daar een prijs in ontvangst te nemen. Het jacht bleek achteraf niet de Priny te zijn maar Topaze. Een vaartuig van 8 ton van 9.10 m met 1.6 diepgang dat toebehoorde aan dhr Gontaut uit Duinkerke. Men vermoedde dat er drie mensenlevens verloren zijn gegaan. Waarom dokter Ballue aan boord was van de Topaze is niet duidelijk.

De Marie-Henriette in droogdok.

In september 1897 werd het stuurboord wiel van de Marie-Henriette in Antwerpen nogmaals vervangen.

Enkele maanden later, op 22 maart 1898 kreeg de administratie van de commandant Vandekerckhove via Dover een telegram dat ze in Dover waren aangekomen en het bakboord wiel volledig los geraakte. Een sleepboot diende hen ter hulp te gaan en kon niet aan de pier aanleggen en voor anker te gaan in de baai. Door het slechte weer kon de Marie-Henriette niet naar Oostende terug keren en werden de volgende geplande reizen afgelast. Enkele dagen later vaarde de Marie-Henriette een vissersschip de O.50 Victor met schipper Cattoor-Molleman aan in de haven. Gelukkig waren er geen gewonden en bleef het enkel tot materiële schade.

Regelmatig deden zich ongevallen voor. Op 20 november 1899 geraakte de Marie-Henriette weer in de problemen met het stuurboord wiel. Die maandagavond had ze Dover verlaten om 23u00 en kreeg problemen. Er diende een sleepboot gestuurd om te helpen. De geplande aankomst van 03u00 werd 10u00 in Oostende.

Op de dag voor kerstmis 1899 lag de Marie-Henriette aan een aanlegpost in Dover voorhaven. De Princesse Henriette was afgevaren in de dikke mist en botste tegen de Marie-Henriette aan die ernstige schade opliep.

Het was zaterdag 27 januari 1901 wanneer de Marie-Henriette nabij Nieuwpoort een blad van haar rad verloor. Het duurde wel 1 ½ uur om het blad te herstellen en verder naar Oostende te kunnen varen.

Commandant Romyn en zijn officieren.

Aan het begin van de zomer 1901 op 4 juni was de Marie-Henriette uit Oostende vertrokken om 10u47. Nabij het lichtschip Ruytingen stond er een dichte mist en de Marie-Henriette voer halve snelheid zoals voorgeschreven. Plotse botste de maalboot met een Frans visserschip uit Gravelingen, de N° 302. Het visserschip gaf geen signalen en dook plots op voor de neus van de maalboot met cdt Vandekerckhove. De maalboot stopte direct maar de Marie-Henriette boorde zich in de zijde van het vissersschip dat onmiddellijk en in enkele seconden zonk. De maalboot kon nog reddingsboten uitzetten en hulplijnen naar de bemanning gooien. Dank zij deze snelle reactie kon de bemanning gered en was het enkel het schip dat verloren was. De Marie-Henriette had weinig schade en was om 03u54 in Dover aangekomen met de overlevenden en de 126 reizigers die aan boord waren. Een Amerikaanse consul Mr Hain uit Antwerpen organiseerde nog een omhaling onder de reizigers voor de slachtoffers. Hij kon nog 345 Fr. aan de overlevende bemanning overhandigen.

Op zaterdag 31 oktober 1901 vond de Léopold II vertrekkende vanuit Oostende de Marie-Henriette ter hoogte van de Ruytingen voor anker. De cdt Vandekerckhove liet weten dat er problemen waren met het wiel maar dat men bezig was het te herstellen. Bij aankomst in Dover liet de Léopold II een telegram sturen naar Oostende om de wachtende gerust te stellen. Het ongeval met het wiel was niet zo erg maar het begon op te vallen. De Marie-Henriette was om 23u00 uit Oostende vertrokken de donderdag 21 november 1901 en bleef uit in Dover. Pas om 08u20 kwam ze aan en had te kampen gehad met mist en problemen met het wiel.

Op 16 december 1901 was ze om 23u00 in Oostende vertrokken wanneer ze voor Nieuwpoort een wrak van redelijk omvang had aangevaren. De schade aan het wiel was ernstig dat de kapitein besloot om terug naar Oostende te keren. De reizigers en zendingen werden op de Ville de Douvres geladen die om 05u00 kon vertrekken.

Tijdens een storm in de nacht van donderdag 30/31 januari 1902 had de Marie-Henriette weer een ongeval met het wiel tijdens het vertrek te Dover om 16u00 en diende voor anker te gaan waar de zee wat kalmer was tot de volgende maandag. Drie dagen en drie nachten is het schip ter plaatse gebleven in de zware storm. De commandant is geen moment van de brug geweest. De omstandigheden moeten heel ernstig geweest zijn want de bemanning werd achteraf onderscheiden voor hun moed en toewijding door de Minister. De reizigers hadden uitvoerig in de pen gekropen en aan de Minister en overheden lof geuit over de professionaliteit van de ganse bemanning.

Op 16 mei 1902 brak deze keer de Marie-Henriette de twee armen van de raderwielen. Heel langzaam diende ze naar Oostende te varen om uit de vaart te gaan. De nodige wielen en stukken werden wederom besteld.

Er deden zich veel problemen voor met de raderwielen van de Marie-Henriette en men dacht aan een constructiefout. Door het ongeval begon men ook in te zien hoe belangrijk het zou worden om de schepen toch met telegrafie uit te rusten. Op 17 juli 1902 werd de telegrafiepost in Nieuwpoort in werking gesteld en was de Marie-Henriette ook uitgerust met een zendstation van het Marconi systeem.

Stilaan werd het tijd voor zware herstellingen. Op 15 april 1903 organiseerde het Zeewezen een openbaren aanbesteding voor het vervaardigen van twee schouwen in zacht staal; een lot ijzeren messen en verschillende stukken in smeedijzer. Cockerill kwam er als duurste uit. Het resultaat was opmerkelijk.:

1. twee schouwen in zacht staal voor de boilers van de pakketboot Marie-Henriette van de Oostende-Dover lijn.

• Chantiers naval, ateliers et fonderies de Nicolaill a Bouffiouix 7.520 Fr.

• Grandes chaudronneries d’Anvers Hoboken 8 500 Fr.

• Brugeoise Brugge 8710 Fr.

• Ateliers de constructions et chaudonneries de Montignies-sur-Sambre 9 795 Fr.

• C. Delsaux uit Boom 9 976 Fr.

• A. Larochaymond Doornik 10 000 Fr.

• Le Vulcain Belge Antwerpen 10 320 Fr.

• Ateliers de Thiriau Bois d’Haine 10 360 Fr.

• The Antwerp Engeneering C° 10 600 Fr.

• Chaudronneries et fonderies de Liège Luik 10 735 Fr.

• Chaudonneries et ateliers de constructions Langlet broeders Keulen 11 950 Fr.

• Societé Cockerill Seraing 11 990 Fr.

2. Vervaardigen van een lot ijzeren messen, verschillende stukken in aangepast smeedijzer, en bouten voor de paddel van de staatspakketboot te Oostende:

1e lot messen 4 985.50 Fr:

• Societé John Cockerill Seraing 4 430 Fr.

2e lot onderdelen 29 820 Fr.:

• Ateliers du Thirian a bois d’Haine 29 820 Fr.

• Grosses forges et usines a Hestre Bume 30 954 Fr

• Societé John Cockerill 31 005 Fr.

3e lot bouten (2 843.28 Fr.)

• A Lemaire-Cartuyvels Herstal 2 306.50 Fr.

• Soc. John Cockerill 2 570 Fr.

• Boulonneries du Haut Pré Luik 2 683.90 Fr

De installatie van de telegrafie wierp duidelijk zijn vruchten af. Op 10 januari 1904 was de Marie-Henriette te Oostende om 23u00 vertrokken wanneer ze na 1 ½ te kampen had met een defect aan de machine. Het schip kon niet meer gestuurd. Dank zij de draadloze telegrafie kon hulp gevraagd en stuurde men onmiddellijk een sleepboot terwijl de Princesse Joséphine werd opgewarmd. Terug in Oostende konden de reizigers en bagage omstreeks 03u00 overstappen waarna full speed naar Dover. De reizigers waren enorm onder de indruk van de snelheid en efficiëntie waarmee men had gehandeld en een andere pakketboot kon ten dienste stellen.

In september 1904 was het weer tijd voor een grote onderhoudsbeurt en droogdok in Antwerpen. Daarna is er een hele tijd weinig van problemen te melden geweest. Op 26 februari 1905 een machinedefect waardoor ze diende voor haar reis vervangen. Echter op 5 juni 1908 was het wel even paniek. De Marie-Henriette diende om 1530 te Oostende te vertrekken maar men vond in het ruim bijna 1 meter water.

Naar aanleiding van een schrijven ontstond er in mei 1912 een ernstig debat over de veiligheidsmiddelen aan boord van de maalboten. Een reiziger had in april een reis met de Marie-Henriette meegemaakt en het tekort aan reddingsmiddelen aangekaart. We merken op dat dit gebeurde na het ongeval met de Titanic op 14/15 april 1912. Toch was het schrijven min of meer terecht. In de Kamer werd hard gedebatteerd over de tekorten. Men beloofde dit op korte termijn te zullen aanpassen en reddingsboten bijplaatsen waar dat kan.

Op 25 maart 1914 lag de Marie-Henriette aan de werkhuizen aan de oostkant van de haven. Enkele dieven hadden het gemunt op koperen buizen en konden een grote hoeveelheid buizen op de Marie-Henriette ontvreemden. Er werd voor 120 Fr. buizen gestolen.

Stilaan naderde het onheil van de grote oorlog. In augustus 1914 deed de Marie-Henriette nog de normale reizen naar Dover tot deze werd gesloten voor commercieel trafiek.

> Op 24 augustus 1914 bracht ze geldreserves van de Nationale Bank van België naar Engeland.

> Vanaf 10 oktober en dit tot 14 oktober nam de Marie-Henriette deel aan de evacuatie van vluchtelingen uit Oostende naar Frankrijk en Engeland.

> De Marie-Henriette was op 14 oktober de laatste boot die Antwerpen verliet bij de evacuatie van die stad.

> Vanaf 16 oktober was Antwerpen in handen van de bezetter.

> Op 17 oktober is ze naar Le Havre afgevaren. Waar ze vanaf 18 oktober is ingezet als hospitaalschip om de gewonden te vervoeren van de Ijzer naar Le Havre. Op de terugreis bracht ze munitie mee uit Cherbourg en bracht deze naar Calais.

> Op 24 oktober onderweg naar Cherbourg liep ze tijdens de nacht op de rotsen bij Barfleur. Het havenlicht was gedoofd en de commandant was hiervan niet op de hoogte. Het schip was totaal verloren

Overblijfselen van de Marie-Henriette nabij Barfleur